Kissinger on Trump and 'The Cunning of Reason'

The Financial Times has a diverting weekly feature - "Lunch with the FT" - in which its correspondents interview some notable person over lunch. You get the human to-and-fro of a sometimes revealing conversation between two individuals. You get appreciative comments about the attractive and vivacious maitre d', the bottle of Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru 2013, the fillet of sea bream poached in layers of leek.

The Financial Times has a diverting weekly feature - "Lunch with the FT" - in which its correspondents interview some notable person over lunch. You get the human to-and-fro of a sometimes revealing conversation between two individuals. You get appreciative comments about the attractive and vivacious maitre d', the bottle of Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru 2013, the fillet of sea bream poached in layers of leek.

Last week the FT's man in Washington Edward Luce had lunch (paywall) with the "grand consigliere of American diplomacy," former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. At 95, Kissinger is not only still alive but "hops on and off planes" to meet the likes of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, is writing a book on great statesmen and women he has known, and charges "princely sums" for his thoughts, through his geopolitical consultancy Kissinger Associates.

Luce is on a mission to find out what Kissinger "really thinks about Donald Trump." The timing he thinks is perfect, the day after Trump's much-reviled summit with Putin in Helsinki. But, despite several attempts to pounce upon his aged quarry, Luce is unable to corner Kissinger into a direct comment on Trump.

Except for this evidently premeditated and striking if cryptic assessment:

"I think Trump may be one of those figures in history who appears from time to time to mark the end of an era and to force it to give up its pretences. It doesn't necessarily mean that he knows this, or that he is considering any great alternative. It could just be an accident."

I make five points. Four are specific to Kissinger on Trump. The last is on the Hegelian model of historical change - the cunning of reason - that Kissinger rather casually deploys here while toying half-heartedly with his branzino (European bass) on a bed of green vegetables.

First, Kissinger thinks Trump may already be a substantial figure in world history, not, alas, some bizarre printer's error that Trump-opponents hope to erase from its pages.

Second, he's not just any historical figure but one who marks the end of an era. This much should be apparent even from Trump's critics, who denounce him for upending the post-war "liberal international order," among other epochal crimes.

Third, Kissinger hints that the era which is ending may indeed deserve to go. Trump is forcing it to give up its pretences. Here one longs for Kissinger to descend from the clouds. Which era, and which pretences? There were not one but two post-war liberal democratic orders. The first prevailed during the Cold War, from say 1948 to 1989. This was an alliance of sovereign liberal-democratic nation-states that sought to contain Soviet communism and to prudently expand the scope of international trade and investment while retaining the main levers of the economy with the nation-state. The second is the 'hyper-globalist' model that the United States, Europe and others adopted after the end of the Cold War, which looks as its ideal to unfettered movement of capital, trade and people in an essentially borderless world, in which the democratic nation-state is stripped of purpose and withers away. Is it this imprudently utopian post-Cold War version of the liberal international order that Trump is forcing to give up its pretences?

Fourth, says Kissinger, Trump could play a world-historical role without necessarily knowing what he is doing. This idea may challenge many Trump-critics, who work with a historical model in which good results can flow only from good people with good intentions, not from some ignorant, amoral "orange-haired baboon."

Fourth, says Kissinger, Trump could play a world-historical role without necessarily knowing what he is doing. This idea may challenge many Trump-critics, who work with a historical model in which good results can flow only from good people with good intentions, not from some ignorant, amoral "orange-haired baboon."

Historic individuals who mark the end of "eras" by forcing them to "give up their pretences," without necessarily being aware of what they are doing - this is a language and dynamic that Kissinger draws from George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's "Lectures on the Philosophy of History" of 1837.

Rather than attempt the technicalities of Hegel's text, which, to be frank, I have not read, I follow a brilliant exposition by the political scientist and historian Robert C. Tucker: "The Cunning of Reason in Hegel and Marx." [1]

"According to Hegel, universal history is the realization of the Idea of Reason in a succession of National Spirits. These are manifested in the deeds of heroes... However, the Idea of Reason does not work itself out in history in a manner which would seem reasonable on the surface. It is not actualized in this or that of its stages as a consequence of men consciously adopting it as their ideal and striving to translate it into reality through their mode of life and conduct. It is not, as it were, through the imitation of Reason that Reason is realized in history. How, then, does this take place?

"Hegel's answer to this question is contained in his doctrine of the Cunning of Reason. Briefly, he holds that history fulfills its ulterior rational designs in an indirect and sly manner. It does so by calling into play the irrational element in human nature, the passions."

Tucker stresses that it is not the ordinary human desires for mere happiness, pleasure or enjoyment that Hegel has in mind here.

For "those world-historic individuals whose passions drive them on to 'deeds of universal scope'...the aim was not to be happy: 'they wanted to be great.' This is the key phrase. When he employs the word 'passions,' Hegel especially has in mind the range of emotions which center in the will to be great: pride, ambition, the love of fame, the craving for power, the urge to conquer. These might be summed up by the phrase 'passion for self-aggrandizement,' and the activity which results under the influence of this passion might be described as a Quest for Mastery."

Sound familiar? In sum:

"Hegel's view is that the passion for self-aggrandizement leads the great men of history to become the instruments of an ulterior rational design of which they themselves may remain oblivious and to which, without being clearly aware of it, they are sacrificed: 'This may be called the cunning of Reason - that it sets the passions to work for itself, while that through which it develops itself pays the penalty and suffers the loss.' ...Thus the Idea of Reason, which is simply the entire scheme of development which the Spirit traverses through human history, is fulfilled in and through the deeds of an individual who is carried away by the passion for self aggrandizement. The Cunning of Reason consists in the fact that the 'particular purposes' of the individual are made to serve the 'substantial will' of the World Spirit."

Should we be surprised to find one of the most consequential American Secretaries of State of the 20th century unleashing Hegelian tropes over lunch at the Jubilee restaurant in Midtown Manhattan?

Perhaps not, especially when we read of those primarily German historians who most influenced Kissinger's intellectual formation as a young academic in the Department of Government at Harvard in the 1940s and early 1950s. William Weber says in an article on "Kissinger as Historian" that "those historians fall into a brand of historicism which began with Hegel and was further modified by Ranke, Meinecke, Spengler and Toynbee." [2].

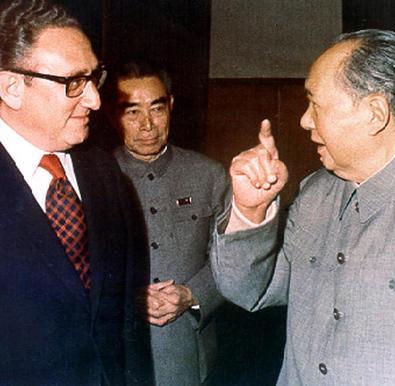

Kissinger himself talked about the influence of Hegel on his thinking in an  astonishingly frank and wide-ranging conversation with Mao Tse-tung, in Beijing, on November 12, 1973:

astonishingly frank and wide-ranging conversation with Mao Tse-tung, in Beijing, on November 12, 1973:

Chairman Mao: And the philosopher of your motherland, Hegel, has said—I don’t know whether it is the correct English translation—”freedom means the knowledge of necessity.”

The Secretary: Yes.

Chairman Mao: Do you pay attention or not to one of the subjects of Hegel’s philosophy, that is, the unity of opposites?

The Secretary: Very much. I was much influenced by Hegel in my philosophic thinking.

Chairman Mao: Both Hegel and Feuerbach, who came a little later after him. They were both great thinkers. And Marxism came partially from them. They were predecessors of Marx. If it were not for Hegel and Feuerbach, there would not be Marxism.

The Secretary: Yes. Marx reversed the tendency of Hegel, but he adopted the basic theory.

Chairman Mao: What kind of doctor are you? Are you a doctor of philosophy?

The Secretary: Yes (laughter).

[1] Robert C. Tucker. "The Cunning of Reason in Hegel and Marx." The Review of Politics. Vol.18, Number 3 (July 1956), pp. 269-295.

[2] William T. Weber. "Kissinger as Historian: A Historiographical Approach to Statesmanship." World Affairs. Vol. 141, Number 1 (Summer 1978), pp. 50-46.